If you’ve spent any time learning the basics of music theory, it’s likely that you’ve heard or seen the words diminished and minor. To the novice, these words seem like they would have similar meanings. However, these two words have very different definitions when it comes to describing music intervals.

A diminished interval is the result of a minor or perfect interval that has been lowered by one half step without a change in its interval number. A minor interval is the result of a major interval that has been lowered by one half step without a change in its interval number.

From these definitions of diminished intervals and minor intervals, one can interpret that each new interval is the result of descending one semitone from a starting interval. So if you know the starting interval and a few rules for renaming intervals when lowering them by one half step, it will be easy to distinguish the difference between diminished intervals and minor intervals.

Note: Half step can be used interchangeably with semitone.

Naming Intervals

An interval’s name is formed by its quality and degree. For example, in a minor third, minor is the interval’s quality and third is the interval's degree.

The quality in an interval’s name is simply how an interval sounds. Diminished intervals (d5, d7) sound unstable or dissonant. And the sound of minor intervals can be either consonant (m3, m6) or dissonant (m2, m7), but all minor intervals have a sad or dark sound.

An interval doesn’t get the degree number in its name from its size in half steps but rather from the order of note names. For instance, in the key of C, G is five letters away from C; therefore, G forms a perfect fifth interval from the root note of C. Staying in the key of C, a diminished fifth is a G♭, not an F♯, because F is four letters away from C. With F as the fourth letter or note in the key of C, a fifth interval cannot be formed between these two letters of the musical alphabet. Any interval between C and F will be a fourth.

So in any seven-note scale, each letter of the musical alphabet is used only once. The used-only-once rule also applies to the interval numbers or degrees of a scale. Therefore, interval number can be used interchangeably with either scale degree or letter. For example, in the key of C:

interval number (5) = scale degree (fifth) = letter (G)

This used-only-once rule is the reason a diminished interval number or minor interval number isn’t changed when lowered a half step from its starting interval.

Starting Intervals

In Western music, there are twelve intervals per octave described by quality and degree. The interval quality can be described as either perfect, minor, major, diminished, or augmented. And within an octave, the interval degrees are unison, second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, and octave.

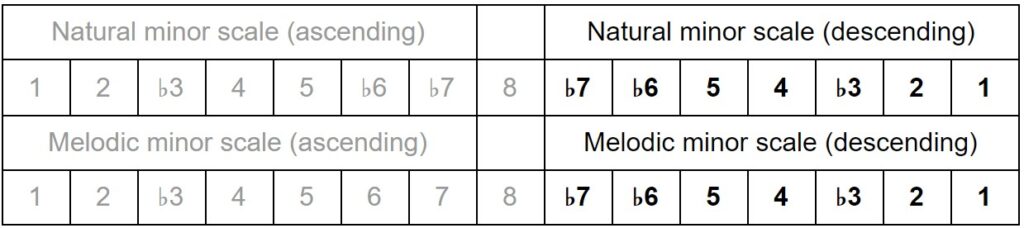

Here are a few rules that will apply when trying to determine whether an interval will become diminished or minor when lowered by one half-step:

To Diminish

- If your starting interval is minor, decreasing the interval size by one half step will create a diminished interval, as long as there is no change in interval degree or number.

- If your starting interval is perfect, decreasing the interval size by one half step will create a diminished interval, as long as there is no change in interval degree or number.

Exception: One cannot decrease the interval size of a perfect unison. Therefore, there is no such thing as a diminished unison.

Note: Diminished is most often used to describe a diminished fifth interval and a diminished seventh interval.

To Make Minor

- If your starting interval is major, decreasing the interval size by one half step will create a minor interval, as long as there is no change in interval degree or number.

Here’s a depiction of what starting intervals become once lowered by one half step:

Table of Diminished Intervals and Minor Intervals

Adhering to the above rules, the following table will list starting intervals that are either minor, major, or perfect. However, the perfect unison will not be listed as a starting interval because there is no such thing as a diminished unison.

Note: This table references only simple intervals or intervals that are less than one octave apart.

*Enharmonically equivalent to a Perfect Unison. For example, E to F♭ is a diminished second, but its sound is enharmonically identical to the perfect unison of E to E.

**Enharmonically equivalent to a Major Seventh interval. For example, C to C♭ is a diminished octave, but its sound is enharmonically identical to the major seventh interval of C to B.

A diminished octave interval would have notes of the same letter name, but each note of the interval would have different accidentals. For instance, in the key of C, C♮ to C♭ would be a diminished octave interval.

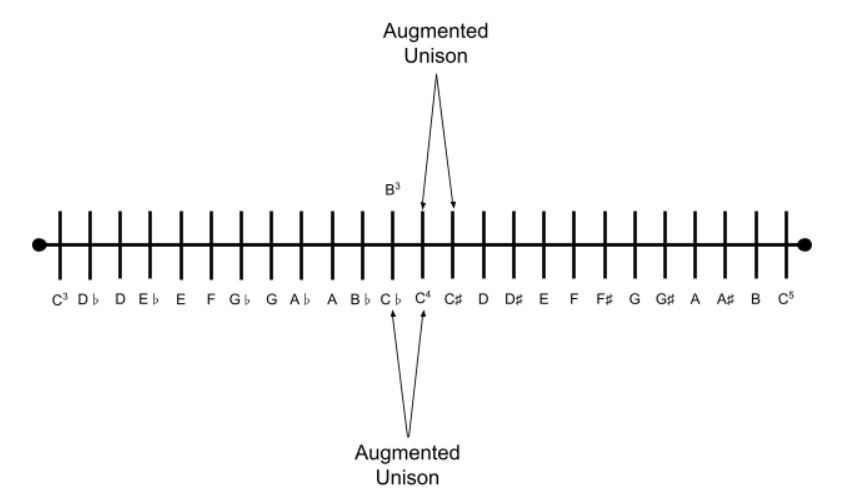

So what about a diminished unison? While an augmented unison exists, there is no such thing as a diminished unison. Let’s use a mathematical model to explain why.

Numbers can be either positive, negative, or zero. Here’s a number line to demonstrate that:

In mathematical terms, any positive or negative number’s distance from zero is that number’s absolute value. The distance from zero (0) to negative one (-1) or from zero (0) to positive one (+1) has an absolute value of one (1).

Intervals aren’t often thought of as positive or negative; however, an interval’s distance can only be positive, unless it’s a perfect unison then the distance between its two notes is zero. So in comparison to a number line, think of an interval’s size or distance in terms of absolute value.

Middle C to middle C is a perfect unison. If one note of this perfect unison interval is lowered by one half step yet remains the same letter or degree (C♭ or unison in this case), it becomes an augmented unison. This is because the distance between the two notes is a positive distance.

Note: C♭ is the enharmonic equivalent of B. However, the interval formed between B3 to C4 (middle C) is a minor second, not an augmented unison. B3 to C4 (middle C) is a minor second interval because there is a difference in the letter names of these two notes.

Conclusion

To recapitulate, if lowering a major interval by one half step, the new interval becomes minor, as long as there is no change in the interval number.

If lowering a minor or perfect interval by one half step, the new interval becomes diminished, as long as there is no change in the interval number.

And remember, there is no such thing as a diminished unison.