Diatonic Intervals Defined

Diatonic is a word derived from two parts: Di is a prefix borrowed from the Greek language that means double, twice, or two, whereas tonic is the first degree of a music scale. And an interval is the distance between two notes. But what does diatonic mean when it’s used as an adjective to describe music intervals?

A diatonic interval is an interval between any two music notes of a diatonic scale. A diatonic scale is a seven-note, Western music scale that has two characteristics:

- It is composed of five whole steps (tones) and two half steps (semitones).

- The five whole tones (whole steps) and two semitones (half steps) form two tetrachords separated by a whole tone.

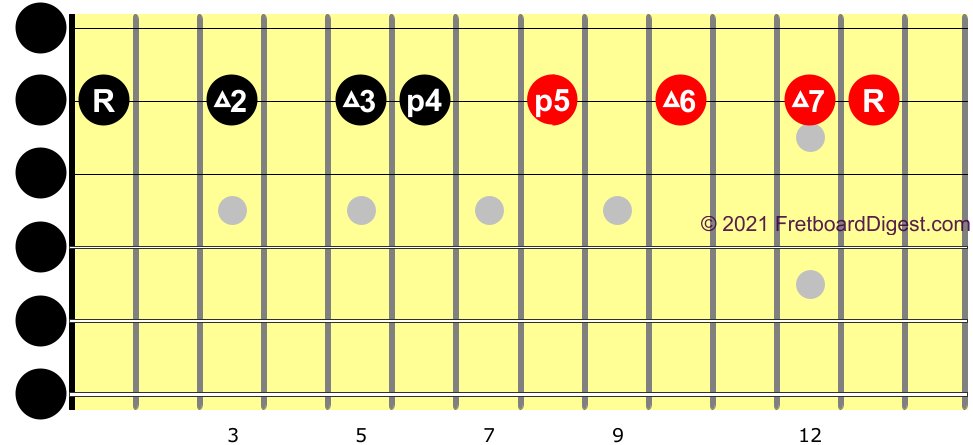

A tetrachord is a series of four notes with the intervals of whole step, whole step, half step. In the C major scale example, above, one tetrachord is in black, while the second tetrachord is in red; the two tetrachords are separated by a whole step between p4 and p5.

Since diatonic intervals can exist between any two music notes of a diatonic scale, there are more diatonic intervals than the five whole steps and two half steps that make up the diatonic scale.

Note: Whole step can be used interchangeably with whole tone, whereas half step can be used interchangeably with semitone.

W = Whole step = T = whole Tone

H = Half step = S = Semitone

Naming Intervals

Music students initially learn that there are two types of diatonic intervals within an octave of the major scale: major and perfect. And they’ll learn that within that octave, there are eight intervals described by quality and degree:

| Quality | Degree | Description |

| Perfect | Unison | two notes of the same pitch played at the same time |

| Major | Second | two notes, one whole step apart |

| Major | Third | two notes, two whole steps apart |

| Perfect | Fourth | two notes, two and a half steps apart |

| Perfect | Fifth | two notes, three and a half steps apart |

| Major | Sixth | two notes, four and a half steps apart |

| Major | Seventh | two notes, five and a half steps apart |

| Perfect | Octave | two notes, six whole steps apart |

These eight intervals usually describe the second note’s distance from the root note in a major scale. However, one can use a diatonic interval from this list to describe the interval between any two notes of a diatonic scale, as long as that interval fits between the two notes. For example, the interval between a perfect fourth and a perfect fifth is a major second.

Each of the five whole tones within a diatonic scale is a major second interval. One interval not in the above list is the minor second interval. Each of the two semitones within a diatonic scale is a minor second interval. Therefore, add minor to the list of interval qualities: major, minor, and perfect.

The natural minor scale is a commonly used diatonic scale (described below) that has three other minor diatonic intervals: minor third, minor sixth, and minor seventh.

Though not very common, there are two other diatonic intervals found in some modes (see below) of the major scale: an augmented fourth and a diminished fifth.

Diatonic Scales

Since a diatonic interval is an interval between any two notes of a diatonic scale, let’s determine what scales are diatonic scales.

The most commonly used scales in Western music are the major scale, the three minor scales (natural, harmonic, melodic), the pentatonic scale, and the blues scale. There are many other scales, but for an introduction to diatonic intervals, only the most common are covered here.

Major

The major scale can be played in seven different modes: Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian, and Locrian. An oversimplified way to think of modes is to consider a major scale (Ionian) starting on its root note, while the other six modes of the major scale start on a different note or degree of the major scale.

All seven modes of the major scale contain diatonic intervals because all seven scales have five whole tones and two semitones that form two tetrachords separated by a whole tone.

For example, here are the seven modes of C major:

| Ionian | C | D | E | F | G | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

| Dorian | C | D | E | F | G | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

| Phrygian | C | D | E | F | G | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

| Lydian | C | D | E | F | G | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

| Mixolydian | C | D | E | F | G | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

| Aeolian | C | D | E | F | G | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

| Locrian | C | D | E | F | G | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

Note: There is a more detailed description of modes, but that is beyond the scope of an introduction to diatonic intervals.

Natural Minor

The natural minor scale (Aeolian mode) is a common scale, and it is one of the seven modes of the major scale. It can be created by using the sixth degree of the major scale as the tonic or root note. And it is a diatonic scale containing diatonic intervals.

Here’s an example of E natural minor compared to G major:

| Scale degree | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 1(8) | |||||

| Major | G | a | b | C | D | e | f♯ | G | |||||

| Interval from previous note | W | W | H | W | W | W | H | ||||||

| Scale degree | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 1(8) | |||||

| Natural minor | e | f♯ | G | a | b | C | D | e | |||||

| Interval from previous note | W | H | W | W | H | W | W |

Harmonic Minor

The harmonic minor is a seven-note scale, but it is not composed of five whole tones and two semitones that form two tetrachords separated by a whole tone. Therefore, it is not a diatonic scale by definition.

The intervals of the harmonic minor scale are shown, below:

Tonic (1) – W – 2 – H – ♭3 – W – 4 – W – 5 – H – ♭6 – W+H – 7 – H – (8) Octave

The Whole plus Half step (W+H) interval between the ♭6 and major 7 is also known as an augmented 2nd. This interval gives the harmonic minor a very unique sound.

Note: Some music theorists will argue that a diatonic scale is a seven-note scale with a tonal center, in which the other six scale notes move towards or away from the tonic. This argument would include the harmonic minor and ascending melodic minor (described, below) as diatonic scales.

Melodic Minor

The ascending and descending scales of melodic minor do not have the same intervals. When some musicians refer to melodic minor, they’re only thinking of the ascending scale. The ascending melodic minor is a seven-note scale, and it is composed of five whole steps and two half steps. However, it does not form two tetrachords separated by a whole tone. Therefore, it is not a diatonic scale, as defined here.

Here are the intervals of the ascending melodic minor scale:

Tonic (1) – W – 2 – H – ♭3 – W – 4 – W – 5 – W – 6 – W – 7 – H – (8) Octave

What about the descending version of the melodic minor scale?

Starting on the octave (8), here are the intervals of the descending melodic minor scale:

Octave (8) – W – ♭7 – W – ♭6 – H – 5 – W – 4 – W – ♭3 – H – 2 – W – (1) Tonic

The descending melodic minor scale is composed of five whole tones and two semitones arranged to form two tetrachords separated by a whole tone. Therefore, it is a diatonic scale composed of diatonic intervals.

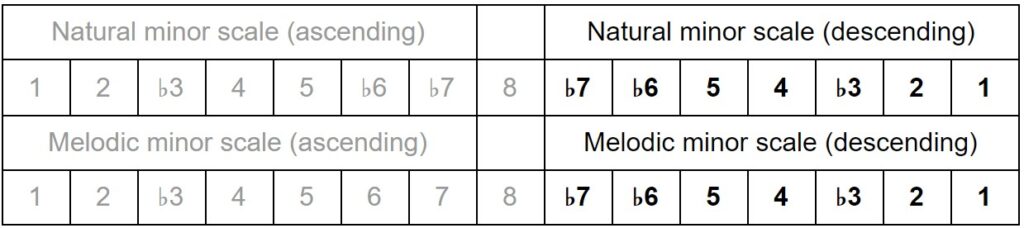

Notice that the descending melodic minor scale is the same as the descending natural minor scale. This is why some musicians won’t call it a descending melodic minor scale.

To see the descending similarity, here’s a table comparing the natural minor scale to the melodic minor scale:

Pentatonic

The pentatonic scale is formed from the major scale; therefore, it has diatonic notes. However, it is a five-note scale, so it is not a diatonic scale.

Blues

The blues scale is a six-note scale, and it’s based on the pentatonic scale. Five of its six notes are diatonic notes; the additional note – the flattened fifth – is a chromatic note or passing tone. Regardless, being a six-note scale, it is not a diatonic scale.

Summary

So if a seven note scale has five whole tones and two semitones that form two tetrachords separated by a whole tone, it has diatonic intervals. But if you hear a musician using diatonic to describe the intervals of harmonic minor or ascending melodic minor, just know that he or she subscribes to a looser definition of diatonic intervals as the intervals of any seven note scale with a tonal center.